Lumbar Spine Bone Stress Injuries and Stress Fractures

What Is a Lumbar Spine Bone Stress Injury ?

As Spring arrives and the weather (hopefully) begins to improve there is a move from indoor training to outdoor training and competition and with it a change in the type and amount of activity and exercise that children and adolescents participate in.

Whilst this is not an issue in itself, how quickly they increase the amount of activity can cause problems.

Most child and adolescent injuries occur not as a result of a collision or a fall or even because they do too much sport. Injuries can occur because they do too much too quickly. The amount of load is greater than the current capacity of the body and without adequate rest and recovery time the bone is unable to adapt and repair.

When the amount of exercise and therefore the amount of load, is greater than the body is used to, the body reacts by laying down extra new bone and muscle as reinforcement. However this process takes time - around 4-6 weeks, to become tough enough to withstand the increased loading.

It is not just reduced capacity that can contribute to injury - growth spurts ( >7cm per year is associated with increased injury risk), illness, tiredness, stress, poor nutrition and low vitamin D are other risk factors.

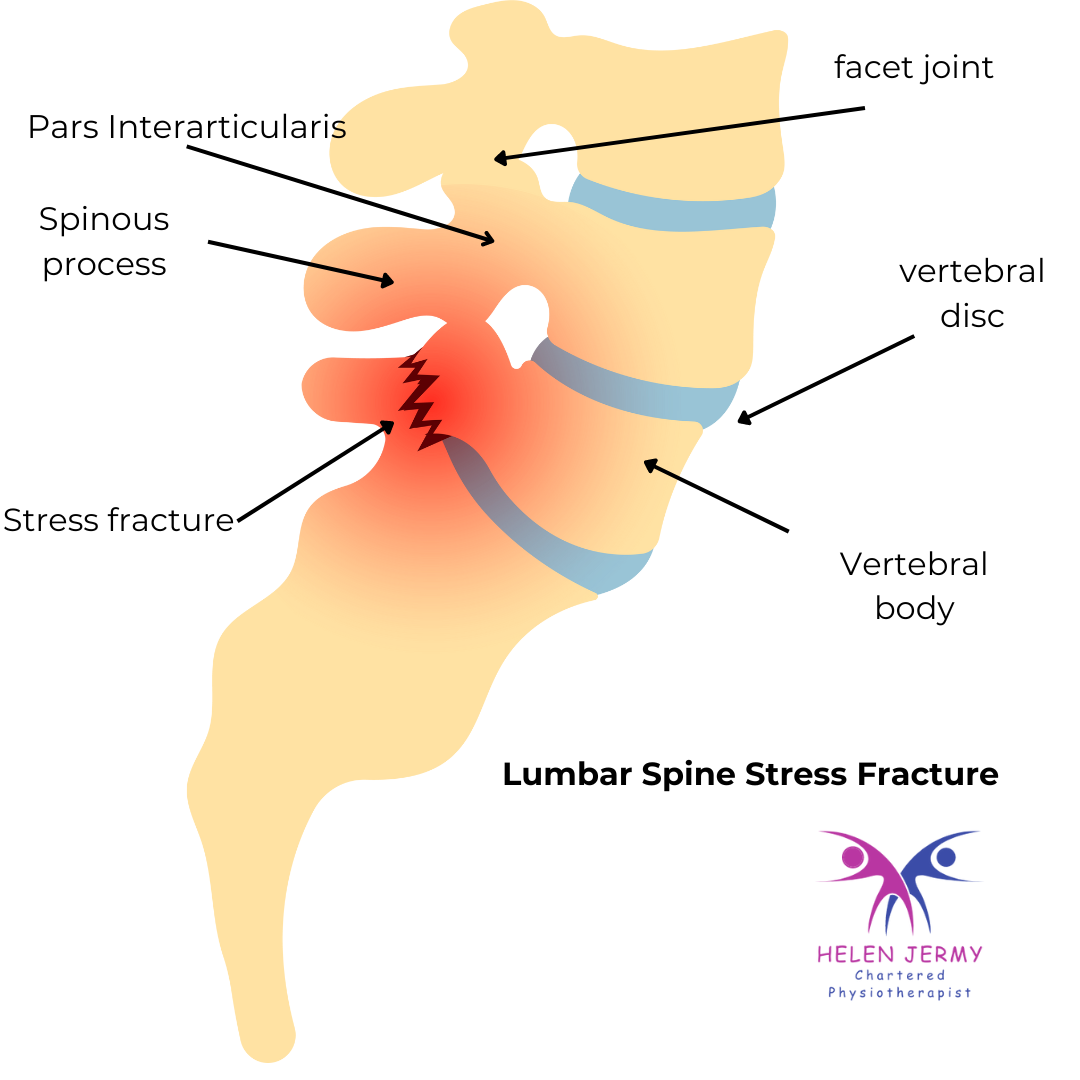

Low back stress fractures occur as a result of repetitive stress on a small bone called the pars interarticularis in the lower back.

As the young athlete grows the pars bone elongates becoming thinner and weaker and can become more vulnerable to injury.

The term fracture is often used but you should think of it more of a stress response, like a bone “bruise” which is quickly reversible if you do the right things in the early stages. In some instances, if the bruise has not had a chance to heal it can progress to a small hairline fracture which takes longer to heal - a stress fracture. EARLY DIAGNOSIS IS KEY

Any young athlete aged 8-23 who is involved in repetitive kicking, overhead sports and sports involving excessive over arching of the lower back is at risk of developing a lumbar stress fracture.

It should be assumed that if a young athlete develops the following symptoms for more than 1 week, it is a stress fracture until proven otherwise:

- Low back pain on the opposite side to the one you throw with

- Pain that gets worse with activity then settles on rest

- Worse on arching backwards, throwing, bowling, running, jumping or kicking and improves with rest

- Pain may spread to both sides and radiate in to the leg

To prevent the bone bruise from progressing to a hairline stress fracture it is important that immediately any lower back pain is felt the athlete stops all activities that hurt for 2 - 4 weeks to allow the bone to heal.

During this period the young athlete should avoid high impact activities such as running or jumping.

- No repetitive extension or rotation of the back eg. kicking, throwing, golf, gymnastics, swim, gym

- No school PE or organised sports.

- No unsupervised gym

Continuing to do activities that are painful can lead to more serious injury and may mean the athlete is out of sport for a much longer period of time.

If it is pain free the athlete can cycle on a static bike to maintain fitness.

It is important to seek the advice of a physiotherapist experienced in treating young athletes with this type of injury for an appropriate strength based training programme and guidance on how to return safely back to sport. Rehabilitation usually involves core strengthening, hamstring stretching and activity modification to avoid additional extension forces on the pars. Strengthening exercises initially focus on static core exercises with a slow progression to flexion then extension based exercises once, ensuring that the exercises are not aggravating any pain. This should be done under the guidance of a physiotherapist.

Most young athletes return to sport 6-12 weeks after a bone stress injury, but once the pain has settled, the volume and intensity of sport and activity should be built up gradually, and not hurry back to pre injury levels of training and competition. Care should be taken to avoid excessive high impact and repetitive activities in the early stages of rehabilitation.

Research has shown that the most common time for injury happens in the first 2-3 weeks of a new sports season.

Too little training and preparation in the pre season period followed by a rapid spike in volume and load puts the young athlete at risk of a bone stress injury in the following 2-3 weeks.

One way of tracking load is by using the acute/chronic workload ratio (ACWR).

- Record all the activity the athlete does in 1 week. You can use minutes of activity/number of throws or balls bowled/km run/lengths swum etc

- Workout the average volume of activity over the past 4 weeks.

- Most young athletes can cope with an increase in volume of 10% on the previous 4 weeks average activity to gradually build up load. You must take into account that there may be a variation in the intensity of some of the session and may put more strain on the body - not every training session is equal and therefore the amount of fuel and recovery needed may vary greatly.

- Alternatively using the ACWR ratio divide the acute load by the chronic load;

For Example;

Week 1 30 high jumps

Week 2 35 high jumps

Week 3 0 high jumps athlete unwell

Week 4 35 high jumps

Total 100 high jumps so average 25 high jumps per week

Week 5 27 high jumps

Acute Chronic Workload Ratio = acute load 27 high jumps / chronic ratio 25 = 1.08

A total workload increase of 8%

For further information on ACWR

If the athletes pain does not settle with rest they may need referral for an MRI scan as X-rays of the lumbar spine are not as sensitive and cannot identify bone stress or ‘bruising’. Further investigation with a CT scan may be necessary to provide more detail

The diagnosis and management of a lumbar spine bone stress injury is extremely important and can be misdiagnosed, affecting long term outcomes and activity levels.

For further advice please contact us